In today's rapidly advancing 5G technology landscape, the competition for Standard Essential Patents (SEPs) has become increasingly intense, with major tech giants and innovative companies vying for dominance. In recent years, high-profile cases such as Huawei v. Conversant, OPPO v. Nokia, and L2 Mobile v. HTC have ignited global debates on SEP patent priority. These cases influence both technological evolution and reveal how courts worldwide are tightening judicial standards for SEP examination.

The rulings from these cases have far-reaching implications, especially the decision in Huawei v. Conversant, where the UK court ruled on FRAND obligations and patent pool licensing rates. This decision has shaken the global patent law community and accelerated a shift in how countries recognize SEP priority. What initially started as a lenient review process has evolved into an increasingly strict judicial attitude, especially in China, where standards for SEP priority examination have undergone profound changes.

In this shifting legal landscape, companies must rethink how they protect and maintain their patent rights and navigate complex patent disputes.

In this article, we will analyze data from 44 Chinese 2G-5G SEP invalidation cases to explore the judicial shift in SEP priority disputes. And through case analysis, we will examine how this shift impacts multinational patent strategies and the global competitive landscape.

Ⅰ. The Uniqueness and Importance of Priority for SEPs

The priority system is a cornerstone of the patent framework, originating from Article 4 of the Paris Convention and the relevant provisions of the PCT. Its core function is to provide a "time window" for multinational patent strategies. Specifically, after the initial patent application is filed (12 months for inventions and utilities, and 6 months for industrial designs), applicants can claim the filing date of the first application (the "priority date") as the reference date for determining novelty in subsequent filings across member countries.

In the context of rapidly evolving technical standards, priority has evolved from a static time point into a dynamic "legal link." This link must navigate the multi-stage process of standard setting (proposal, freeze, implementation) while addressing institutional differences across jurisdictions. Companies must integrate priority management with standard evolution through priority chains, multi-version coverage strategies, and dynamic risk monitoring. This strategy ensures that "patents lead the way before standards are set, and rights evolve in sync with standard iterations," giving companies a competitive edge in the global SEP market.

If an SEP is determined to be ineligible for priority, its novelty is directly challenged, resulting in the invalidation of the patent and triggering a collapse in multinational patent strategies. Therefore, the judicial dynamics surrounding priority disputes have significant implications for companies' legal risk management and business strategy.

Ⅱ. Statistical Analysis of Priority Disputes in SEP Invalidation Decisions

Based on Darts-IP data, we conducted a statistical analysis of all 2G-5G SEP invalidation cases in China (communication generations: 2G-5G; case type: invalidation proceedings; jurisdiction: China; statistical period: up to February 15, 2025). Among the cases involving priority disputes, 44 invalidation cases were identified. In the final invalidation decisions, 23 cases were deemed eligible for priority, 19 cases were deemed ineligible, and 2 cases involved partial priority rights.

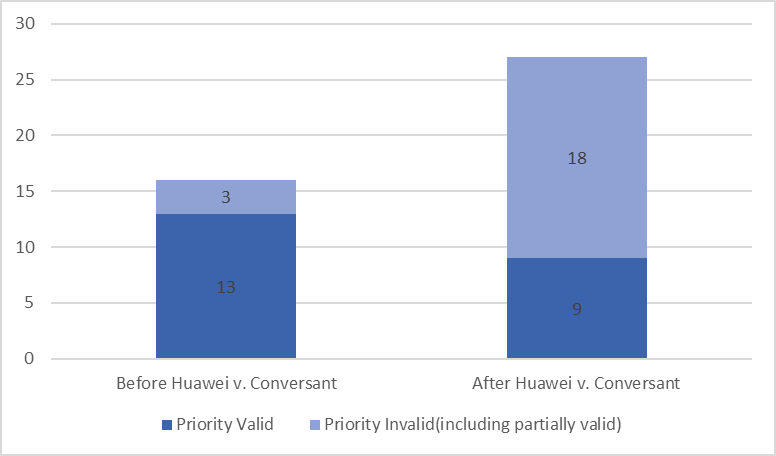

The number of cases ruled ineligible for priority has significantly increased over the past five years. Following the 2019 Huawei v. Conversant case (Supreme Court Case No. (2019) Zhixing 191), a clear shift in judicial attitude is evident. Before this case, 16 priority dispute cases were examined, with only one case ruled ineligible for priority, two cases partially eligible, and 13 cases granted priority (81.25%). However, after this case, 27 priority dispute cases were reviewed, with 18 cases ruled ineligible for priority and only 9 granted priority, reducing the percentage of cases granted priority to 33.33%. Notably, all cases deemed ineligible for priority in the reexamination invalidation decisions were fully supported by the courts in subsequent appeals.

Figure 1: Huawei v. Conversant - Priority Determination in Invalidation Decisions Before and After

This trend suggests that after the 2019 Huawei v. Conversant case, as Chinese telecom companies expand into overseas markets, the number of infringement lawsuits and the associated compensation amounts related to SEPs have increased. Consequently, Chinese judicial authorities have become more cautious in their priority examinations, focusing particularly on the feasibility of technical solutions and the clarity of patent documentation.

Since the Huawei v. Conversant case, the standards for determining priority have significantly tightened, with the percentage of cases granted priority dropping sharply from 81.25% to 33.33%. Cases such as OPPO v. Nokia and L2 Mobile v. HTC demonstrate two core judicial review principles:

1) the need for substantive verification of the "feasibility of the technical solution" in priority documents; and

2) extreme strictness in determining the "direct and unequivocal identification" of the standard.

Global patent offices are aligning their approach to priority examination (for example, consistent rulings in similar cases in China and Europe). If companies fail to synchronize their standard proposals and patent filings with "zero-lag" coordination, they risk the collapse of their multinational patent strategies. In the latter stages of the SEP dispute game, priority disputes have become a "nuclear weapon" in invalidation offense and defense.

Ⅲ. Analysis of Typical Cases: Judicial Standards for Determining Priority

The Patent Examination Guidelines provide substantive provisions for priority:

"An invention or utility model of the same subject matter, as described in Article 29 of the Patent Law, refers to an invention or utility model addressing the same technical field, problem, solution, and expected effect. However, 'the same' does not mean identical descriptions or presentation styles" (Section 2, Chapter 3, 4.1.2 of the Guidelines).

"To determine whether the technical solutions described in the claims of the subsequent application are clearly disclosed in the prior application documents (excluding the abstract), the examiner should analyze the prior application as a whole. If the prior application clearly discloses the technical solution described in the claims of the subsequent application, it should be recognized that both applications involve the same subject matter... Clear disclosure does not require exact consistency in presentation; it is sufficient if the technical solution is explained. However, if the prior application provides a vague or general description of specific technical features, and the subsequent application adds detailed descriptions that a person skilled in the art cannot directly and unequivocally derive from the prior application, the prior application cannot serve as the basis for priority" (Section 2, Chapter 8, 4.6.2 of the Guidelines).

Case 1: Feasibility of the Technical Solution in the Priority Claim – OPPO v. Nokia (2020, Case No. 4W112687)

This case involves a patent invalidation dispute between OPPO Guangdong Mobile Communications Co., Ltd. and Nokia Technologies. OPPO argued that the independent claims of the patent were not entitled to priority. The Reexamination and Invalidation Examination Department supported this argument, leading to the invalidation of the claims. The 3GPP standard was cited as evidence for the lack of inventiveness, with the premise that the patent claims were not entitled to priority.

Claim 1 of the contested patent reads as follows:

If both user equipment (UE) and service cell support 64 Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (64QAM), then the modulation indicator bits are interpreted as Orthogonal Phase Shift Keying/Quadrature Amplitude Modulation (QPSK/xQAM) indicators under the following conditions:

The priority text’s abstract introduced the technical solution outlined in claim 1. Example 2 in the priority document described a specific solution related to this. However, during the oral hearing and invalidation proceedings, the panel conducted a detailed mathematical analysis demonstrating that Example 2 in the prior application was not feasible. As a result, the panel concluded that the prior application only described the "use of 6 bits for code set information, with 1 bit used for 16QAM/64QAM selection," but did not address the technical problem this solution was intended to solve.

As a result, the prior application was deemed to lack concrete implementation of the technical solution in claim 1. The description in the priority document was considered vague, and thus, the addition of specific implementation examples in the contested patent was regarded as a new, detailed description. Consequently, the patent was deemed ineligible for priority from the priority document.

The unique aspect of this case is that while Claim 1 of the contested patent had identical wording to the prior application, the prior application lacked a clear and feasible implementation, preventing it from achieving the intended technical effects or solving the relevant technical problem. This led the panel to classify the prior application as containing a vague or general description. Due to the deficiencies in the priority document itself, the subsequent application could not claim priority. It is also noteworthy that the European counterpart of the contested patent was invalidated by the European Patent Office in the second instance based on the same reasoning.

Case 2: Compression of Interpretation Space – L2 Mobile v. HTC (2019-2020, Case No. (2019) Jing 73 Xing Chu 4650)

In this case, L2 Mobile Technology Co., Ltd. is the patent holder, and HTC Corporation is the petitioner. HTC argued that independent claims 1 and 6 of the contested patent were not entitled to priority. The Reexamination and Invalidation Examination Department agreed with this position, leading to the invalidation of all claims. The invalidation was based on a lack of inventiveness, with the 3GPP proposal cited as evidence.

Claim 1 of the contested patent, as granted, is described as follows:

a wireless resource control connection establishment procedure and a wireless resource control connection re-establishment procedure, both requiring a random access preamble to begin. The method includes:

During the invalidation process, the key dispute centered on whether the priority document clearly disclosed the feature of "immediately re-executing the random access preamble." The petitioner argued that the prior application only described how the UE (user equipment) could restart the current RRC (Radio Resource Control) procedure earlier, but did not mention "immediate re-execution." They also contended that a person skilled in the art would not be able to directly and unequivocally derive this feature from the prior application.

The patent holder, on the other hand, argued that the prior application’s description ("if the competition result message is received, the UE should re-execute the RRC connection establishment procedure") could be interpreted as a computer code "if...then..." statement. Furthermore, in the context of the 3GPP standard, "shall...if..." is equivalent to "immediately," and thus, a person skilled in the art could directly and unequivocally understand the meaning of "immediately re-execute the random access preamble" in claim 1.

However, the panel rejected the patent holder's argument. They found that the prior application did not clearly disclose the feature of "immediately re-executing the random access preamble." While the prior application mentioned how the UE could restart the RRC procedure earlier, it lacked a detailed implementation plan. As a result, the claims were determined to be ineligible for priority.

This case underscores the tightening of the "direct and unequivocal determination" standard for priority recognition and the narrowing of the interpretative space. The prior application did not clearly disclose the technical feature, and thus, the claims in the subsequent application were not entitled to priority.

Case 3: Boundaries of Generalization in Subsequent Applications – OPPO v. Nokia (2022, Case No. 4W113438)

In this case, the patent invalidation dispute arose between OPPO Guangdong Mobile Communications Co., Ltd. and Nokia Technologies. OPPO argued that the contested patent should not be entitled to priority, a position supported by the Reexamination and Invalidation Examination Department. Ultimately, all claims were invalidated due to a lack of inventiveness, with the 3GPP standard cited as evidence.

The central issue in this case was whether the modified independent claims in the subsequent application, which included the feature of "using at least one predetermined sequence and its cyclic shift to arrange the data-independent control signaling information, and where different data-independent control signaling information is separated by at least one cyclic shift of the predetermined sequence and block extension codes," were clearly disclosed in the prior application.

The Reexamination and Invalidation Examination Department concluded that the contested patent used a generalized expression: "using at least one predetermined sequence and its cyclic shift." However, the prior application only disclosed examples of CAZAC sequences. The claims in the contested patent involved a technical solution that was not disclosed in the prior application, such as using other sequences or multiple sequences along with their cyclic shifts to arrange the data-independent control signaling information. This included other embodiments described in the subsequent application, such as the use of the "ZAC (Zero Autocorrelation)" sequence and "RAZAC (Random ZAC)" sequence and their cyclic shifts.

As a result, the contested patent could not claim priority from the prior application. The Reexamination and Invalidation Examination Department's decision was based on the fact that the generalized expression introduced a new technical solution that could not be unequivocally derived from the prior application.

In this case, the Reexamination and Invalidation Examination Department’s judgment was still limited to the text disclosed in the prior application. Although the contested application mentioned in the description that "for example, based on computer-searchable ZAC (Zero Autocorrelation) sequences," and noted that "in terms of zero autocorrelation (or 'close to zero autocorrelation'), the characteristics of the ZAC sequence are similar to those of the CAZAC sequence; it is suggested to use specific computer-searchable ZAC sequences for demodulation of reference signals in LTE UL and for sequence modulation on PUCCH (i.e., the application of the present invention). Currently, there is a proposal to include this sequence set in the LTE standard. These sequences are disclosed in the 2007E02646 FI, 'Low PAR Zero Autocorrelation Region Sequences for Multi-Code Sequence Modulation.' The term RAZAC (Random ZAC) is used in the 2007E02646 FI. However, this term has not been fully established yet," which explains the similarity between CAZAC and other sequences, and from an engineering perspective, it can be concluded that using alternative sequences would still allow the method described in claim 1 of the contested patent to be implemented.

However, the Reexamination and Invalidation Examination Department's judgment remained confined to the text disclosed in the prior application. The generalized expression was deemed to introduce a new technical solution that could not be directly and unequivocally determined. Any attempt to extend the scope of protection through interpretation or generalization was not sufficient to secure priority.

Ⅳ. Conclusion

The data analysis and case studies above make it clear that:

1) After the Huawei v. Conversant case, both the Reexamination and Invalidation Examination Department and various courts have generally adopted a conservative and cautious approach to priority disputes.

2) The rulings and decisions are showing a global convergence trend. For example, the conclusion in Case 1, which denied priority, directly influenced the European Patent Office’s second-instance ruling, where the same reasoning was applied to invalidate the patent. This has affected the stability of family patents in Europe.

The tightening of priority standards, coupled with the global trend toward convergence, poses a significant challenge for patent holders. Companies need to reconsider the relationship between SEP (Standard Essential Patent) patents and standard proposals, and adjust their global strategies accordingly. At the SEP generation stage, patent holders should establish a more precise "standard proposal - patent application" synchronization mechanism, ensuring that each technical proposal from the standardization committee is closely tied to the patent application timeline. By anchoring the evolution of foundational patents and submitting continuations alongside standard updates, patent holders can ensure that the timeline is accurately synchronized. Additionally, the technical solution should be complete and structured, forming a closed-loop argument of technical issues, solutions, and effects. The text should also leave room for interpreting technical features, while adapting to the rules of different legal jurisdictions.

On the other hand, the tightening of examination standards is favorable for invalidation petitioners. Priority disputes are set to become crucial tools in future patent invalidation and litigation battles. To mitigate the risk of priority challenges, patent holders should proactively conduct retrospective priority checks for granted SEPs and manage them with a focus on validity. For core SEP patents with deficiencies, they should initiate divisional applications and priority restoration procedures. Patent holders could also consider creating a predictive database for evaluating priority validity, collecting global family patent examination records, and forecasting judicial review trends. Lastly, patent holders should strategically use priority disputes as a tool for invalidation, as demonstrated in the OPPO cases, by attacking competitors' core patents for priority defects.

Ultimately, in the increasingly fierce SEP battle, priority is not just a legal issue but a strategic factor that plays a crucial role in maintaining a competitive edge in the global market. Only by deeply integrating standard evolution with patent practice can companies secure a strong position in global competition.

Author Bio

Mr. Yuteng Gao has over 8 years of experience in intellectual property, specializing in communications, image, and video technologies. He currently focuses on technical analysis, patent evaluation, and related issues in SEPs. Prior to joining PurpleVine, Mr. Gao served as a patent examiner at the Patent Office of the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA), where he gained expertise in substantive patent examination, application of legal provisions, reexamination, and invalidation. He graduated from the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, holding a Bachelor's degree in Communication Engineering and a Master's degree in Communication and Information Systems. He can be contacted at yuteng.gao@purplevineip.com.